Kolyma Kennels

Introduction

This will be an effort to bring you somewhat closer to a sled dog breed which lies very close to my heart.

It is clear that I will not be able to catch this issue in one episode. It's not even likely that I will be able to capture this topic in these articles at all.

See it as an attempt, an attempt which will consist of four parts:

1. brief historical overview and current state of affairs.

2. the physical of the working sled dog.

3. their mental makeup.

4. their appearance.

Brief Historical Overview.

Let me take you back to the recent history of this breed.

Recent history, because when I tell you that the family tree of the good dogs out of the race kennels in America (Lombard, Norris, Slocum, Seely and McFaul) often within six generations come up in their pedigrees with names like Harry, Dolly, Kreevanka, Kolyma, Tanta, Duke and Togo. Behind these dogs you will find “parents unknown” or “Siberian import".

These were the dogs which mushers like the Johnson brothers and Ramsey (and later Leonard Seppala and Swenson) imported directly from Siberia. Dogs which are the foundation of this breed. So we might consider this a young breed but then, how far back have the people on Kamchatka Island used them up till this moment? Will we ever know? A young breed but timelessly old as well.

Why were these dogs imported from Siberia around the turn of the 20th century? What was the motivation for people like Ironman Johnson and his brother Charlie, Seppala and the Scottish nobleman Ramsey to cross the Bering Street specifically for these types of dogs?

The nature of sled dog needed in Alaska began to change. Faster dogs were needed for faster forms of transport like mail, medication or small food supplies. The trails from village to village were well maintained as were the trails the trappers used to harvest the catch in the traps set out by them. The fur trade was very important both for peoples clothing as their income. And then there were the All Alaskan Sweepstakes. Sled dog races over long distances with prize money for the musher and his team. A welcome addition of the budget.

Well maintained trails created the possibility to hook two dogs up next to each other along the central line connected to the sled – the tandem-hitch - instead of the fan-hitch or Greenland formation mostly in use at that time, where each dog was connected to the sled itself with lines of different lengths. And thus faster and larger teams were possible. Faster dogs needed. Dogs that could combine speed with endurance. A speed which could be maintained over long distances. Dogs which by their conformation and temperament would be able to maintain a fast loping trot changing into full gallop if circumstances allowed it.

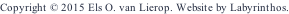

Leonard Seppala.

Freighter and successful musher of the race scene between 1914-1933. One of the most important founders of the Siberian Husky as AKC recognized breed (1930), he died in 1967.

The sled dog which was used at that time in Alaska, were considerably heavier dogs. The Alaskan Malamute and crosses. A breed able to pull heavy loads at a slower pace over long distances. They still participate successfully in freight competitions today. A joy to watch these big smiling guys throw their full weight into their harness taking home as much dog food bags they are able to move loaded on their sled. A different kind of sled dog work for which a different type of dog was bred.

In the Siberian region of that period, especially in that part which is geographically close to Alaska, the Anadyr and Kolyma rivers, Nomad Tribes were able to survive under often extreme conditions. Hunting was their main source of food and survival. Hunting large and fast moving animals. Great distances had to be covered and fast sled dogs needed to keep up with them. All of us who ever met a Moose (American Elk) or an Elk in Scandinavia knows at what amazingly speed these animals can move in deep snow. The only means of transportation for these Nomads were their sled dog teams. Adapted to the needs of these people, the climate and the countryside.

Alaska is situated close to Siberia and the Alaskans had heard about these dogs. They had seen them as well when a trader between both countries named Goosak participated with his team in the Alaskan Sweepstakes in 1909 and finished third. Mushers like Ramsey and Johnson crossed the Bering Straits themselves and came back with dogs. Dogs that were specifically selected for their Alaskan Sweepstake teams with which they participated in the next Alaskan Sweepstakes of 1910 - length of the trail around 700 km. from Nome to Candle and back.

Ramsey imported around 60 dogs from Siberia. He entered a team of the best dogs. Charlie and John (Iron Man) Johnsons teams consisted of the dogs Ramsey did not use. Charley and John started first, Ramsey and the other four participants followed. When the halfway times came through they were considered a mistake, but when the teams crossed the finish line in Nome with times of 74 hours (John) and 76 hours (Ramsey), while the rest of the field arrived the next day, the Siberian Husky had proven itself convincingly. The only other team that was able to keep up with Ramsay en Johnson was that of Scotty Allan. He had specially bred Alaskan crossbred dogs.

A few years later Leonard Seppala appeared on the Alaskan sled dog scene. A Norwegian, who was immediately taken in by these independent, tolerant and quiet dogs with their often bright blue eyes. He also imported Siberians Huskies from Siberia and was very successful with them in the Alaskan Sweepstakes. Seppala used several of Johnson’s males for breeding. Fortunately for the breed, Seppala took his dogs to the “Lower USA” as the rest of the US will always be called by the Alaskans. This took place around 1928, where in New England (Boston, etc.) sled dog races were organised. During the Winter Olympics in Lake Placid in 1932 sled dog racing was part of the program as a demonstration sport in which Seppala participated.

It was these dogs which formed the basis for our breed and were officially recognized as the Siberian Husky Breed in 1930 by the American Kennel Club (A.K.C.). The dogs Seppala, Ironman Johnson and Ramsey imported from Siberia. Dogs which had proven themselves by winning the All Alaskan Sweepstakes.

Dogs that were used as working sled dogs when not participating in the races. Many of Seppala’s dogs were used for breeding or bought from him by “Short” Seeley (Chinook kennels), Harry Wheeler, Bill Shearer and Elizabeth Ricker. They continued breeding and working the breed, and many descendants of these dogs have formed the foundation of kennels as “Igloo Pak” (Dr. Roland Lombard), Alaskan kennels “of Anadyr” (Earl & Natalie Norris), “of Seppala” (McFaul) and “Monadnock” (Lorna Demidoff). The first two kennels were at the top of the sled dog sport for most of the 20th century. McFaul's dogs were sold to Alaskan kennels (half), the other half was purchased by Malcolm McDoughal. These dogs had (and many of their descendents still have) the conformation and drive of the original imports from Siberia and still were put to work in expeditions and participated in the top of the sled dog sport in Alaska and the USA. The Monadnock-kennel started to breed for dog shows only after the 2nd World War.

We limited our import of Siberian Huskies to the Alaskan Kennels “of Anadyr” stock as these dogs were used as sled dogs and bred for participating in the toughest races in Alaska. These dogs were, or were offspring of, proven sled dogs. We imported approximately 80 dogs in total between 1965–1980.

One of Seppala’s Siberian Husky teams, c.1920. Some of these dogs were sold of used for breeding in kennels in the Lower USA.

Current State of Affairs

What became of the Siberian Husky as a sled dog over the past years? As a working dog? Much... and actually not much. Used as a working sled dog of old, he has been replaced by the “iron dog sled”, the motorized sled. Fortunately, not everywhere, because, as many Eskimo and Indian discovered “A Skidoo smells no water. It does not warn of hidden water under thin ice.” Furthermore the Skidoo is very noisy, can break down and gasoline is often very expensive and harder to come by than dog food.

But apart from the above, sled dog sport became very popular in a country where few other amusement and sports was available or possible in winters which took from early October to well into April. Prize money, dog food or other natural prizes could be won. An interesting and welcome addition to the budget.

That long distance races, such as the legendary All Alaskan Sweepstakes, became harder to realize, even in Alaska, is understandable. However, when sled dogs can maintain a high average speed over a race trail of 25 to 40 kilometres per day over 3 days, there is no doubt that these teams can easily run larger distances at a lower average speed.

Or do you question the fact that our top speed skaters of which many hold world records are not able to finish or even win our famous Elf Steden Tocht (Eleven Cities Tour) of 200 km.? Of course they can, they can skate. All it takes is a different kind of training. A different kind of mental approach.

The same applies to the Siberian Husky. A well trained sled dog can run. All it takes is a different kind of training for the different kind of races one wants to participate in. To be successful in the long distance or speed sled dog sport, just like being successful in long-distance or speed skating, takes good athletes. Not every skater can win, not every sled dog can win. But that does not mean that the average Dutch skater (more than half of the Dutch population can skate) or the average Siberian Husky (more than 50% of them likes to pull a sled or rig) cannot have a lot of healthy outdoor fun in their sport.

For winning however, a certain athlete or sled dog is needed. A certain conformation with a certain kind of temperament. In sled dog sport it is called “drive”. Ramsey and Seppala went to Siberia for that kind of dog, and that kind of dog has formed the foundation of the Siberian Husky. To conform these Siberians, the American Kennel Club (AKC) laid down the official Breed Standard of the Siberian Husky. The breed standard as it stands today.

But what is expected from the sled dog today? What is needed to compete successfully in today’s races? What quality dog is needed?

Ch Kodiak av Brattalid. Owned by Benedicte Ingstad Sandberg, daughter of the famous Norwegian archaeologist and writer Dr. Helge Ingstad.

Dr. Ingstad obtained three Siberian Huskies - Sepp, Cindy and Molinka of Bowlake - in 1958 from Leonard Seppala himself . Several Anadyr Siberians were imported shortly thereafter - Alaskans Jet Pilot of Anadyr for one - which formed the basic stock of the Norwegian Siberian Husky population of today.

Photo courtesy Benedicte Ingstad.

Hundreds of sled dog races are organised on the North American and Canadian continent every weekend from October to well into March, as in Europe today. From open class races to all kind of special ones over different distances and several days. Important races are held deeper into the season. Long-distance races are held over several days. The most famous of these is the Iditarod. Run along the trails of the famous Serum Run every year in the second week of March from Anchorage to Nome. Reliving and honouring the mushers that accomplished this memorable feat in the beginning of the 20th century. However, it is not the only one. Canada has the Yukon Quest and the Southern States of America as well as in Scandinavia and the Alps there are several long distance races organized with substantial Siberian Husky teams as this type of race goes back to the origin of the breed for which the dog was imported from Siberia in the first place.

Taking all this into consideration the better speed racing teams reach an average speed of 25-28 kilometres per hour. In the first kilometre some might reach between 35 and 40 kilometres per hour. The temperature and snow conditions, of course, play a role. (It is remarkable that the fastest times of the top teams in multi-day races often be made on the last day of the race). In these areas temperatures in the winter generally can vary between plus 5° C to minus 40° c. In the New England area as well as in Alaska temperatures are often higher than one would expect. It is in the interior of Alaska and Canada specifically that temperatures can drop very low.

The sled dog races therefore focus on early spring or late fall when the interior of the land has been warmed up by the sun. Apart from the specifically speed races where the sled dogs are expected to maintain the above mentioned average speed, the long distance races are organised over several days - sometimes more than a week - with trails leading more inland and teams have to stay alongside the trail for rest and make camp overnight. For these kinds of races the Siberian Husky is very well suited with his thick double coat and strong feet. These races come close to its original origin and work. His conformation enabling him to stay in this Sustained Gallop or Travelling Lope over long distances.

Keep in mind however that in all these kind of races the so-called Alaskan Huskies, Coonhounds, Irish Setters, Foxhounds (American), Husky-Malamute-crossings and crossings of all these breeds themselves participate as well. After all: “A sled dog is a dog who wants to run in front of a sled.” Remarkable however is that the majority of these dogs tend to come close in conformation to those of the Siberian Husky Breed Standard.

Regrettable as it is - with due respect to those breeders who do make the effort to breed and preserve the sled dog qualities in the Siberian Husky breed - the Siberian Husky in its original conformation and workability has lost considerable ground over the past 60 years. Show dogs took over, selected for their eye and coat colour or a combination thereof, not for their performance in harness. But then, is this not the problem and fate of almost all working dog breeds?

Should not the breed dog exhibitions and thus the judges judging those dogs, be held accountable for a large part for the loss of work abilities and health problems with which so many breeds are confronted nowadays? In some cases to an almost total destruction of the breed as a whole? A sad example is the Cavalier King Charles breed... skulls too small to contain their brains as the judges kept putting those dogs up in the show ring with shorter and shorter muzzles. Some of these poor dogs have to be put down because they suffered such pain they could hardly function normally. Luckily for the Siberian Husky breed however there are some outstanding kennels in the U.S., Canada and Europe who stick to their cause, willing to fight this uphill battle and are doing an excellent job in this respect.

Back to the working Siberian Husky. There are race organisations that restrict their races to the purebred sled dog breeds only. This is a good thing in my opinion. Competition in the Open Races is good but testing your dogs against your fellow competitors who have this additional idealism for their specific Polar Dog Breed in mind is needed as well.

I would like take the opportunity to conclude this first part to get a persistent misunderstanding out off the way - the picture of bearded fierce mushers driving their dogs to the limit with whips, etc. - forget that Jack London story! Among the participants are Eskimos, Native Americans and people like you and me, along with veterinarians, engineers, dentists etc. People who love and respect their dogs, knowing that without proper diet and care no good performance can be expected of them.

Maintaining sled dogs is very costly and takes total commitment. Much money has to be invested in equipment and kennel setup. Not to mention the breeding programs and the time and patience it all takes. A good sled dog is very valuable, it will be able to perform well in a team from 2 to 8 years of age. After that its experience is very valuable in helping train the young ones. And they have a normal life span as long as every other dog. Training and care are carefully thought out and executed. There is a lot of literature available and the magazine Team and Trail and many other magazines nowadays that specialize and publish specific training and feeding programs.

As said before however, as with other sports it is only a selected few given to really reach the top in their sport. But the majority of the mushers do not specifically pursue this pinnacle, but find satisfaction and great joy in competing with their own team, as good as possible, is evident. The joy of running your dogs over a specifically for organised race and prepared trail, meet your fellow mushers, be part of the inspiring event that every race is an experience in itself and worth all the effort.

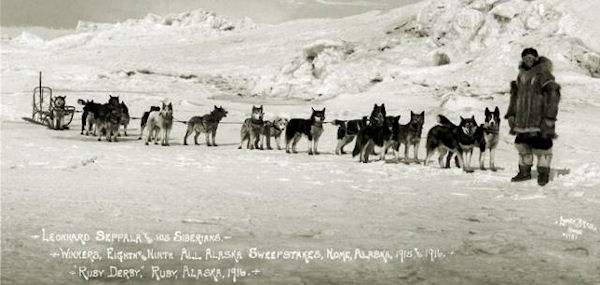

Mt.McKinley Expedition 1945.

Earl Norris with his sled dog team of Alaskan Malamutes, Alaskan Huskies, Siberian Huskies.

Photo courtesy Earl and Natalie Norris.

Sources :

Dr. Roland Lombard: Veterinarian in Wayland, Massachusetts. 7 x World champion. 6 x North American Champion. Sled dog kennel since 1930 (± 80 dogs). 25 years racing experience.

Earl Norris: Sled dog Kennel since 1938 (± 250 dogs) 2 x World Champion. Many times top 3-teams finishes. 25 years racing experience. Expedition experience (Mount McKinley).

Natalie Norris: Imported the first A.K.C. registered Siberian Huskies in Alaska in (1946). North American Champion 1970 (Ladies) with an all registered Siberian Husky Team. Many publications about the Working Siberian Husky . A.K.C. judge for the Siberian Husky and Alaskan Malamute.

Article in The World “Inbreeding" by Dr. E. Daglish.

ISHC - presents the Siberian Husky: published 1969.

The Great Dog Races of Nome: published in 1909 and 1916 by Esther Birdsall Darling.

The Siberian Husky: Research & History. by Foley & Thompson.

The Dog in Action: by McDowell Lyon.

The Alaskan Mushers Annual: published by Greater Anchorage incorporated. Year 1952 - 1971.

Publications in magazines:

Team & Trail: the Mushers monthly news.

ISDRA (International Sleddog and Racing Association).

SHCA Newsletter.

ISHC Newsletter.

The Siberian Husky

Its origin, its work, its mental makeup, its exterior conformation.

By Els van Lierop & Lew van Leeuwen.

Editors note: this article was originally published - in three parts - in the Dutch De Hondenwereld magazine (1968 ). Some things no longer relevant have been left out from the original text and the use of language has been modernised somewhat.